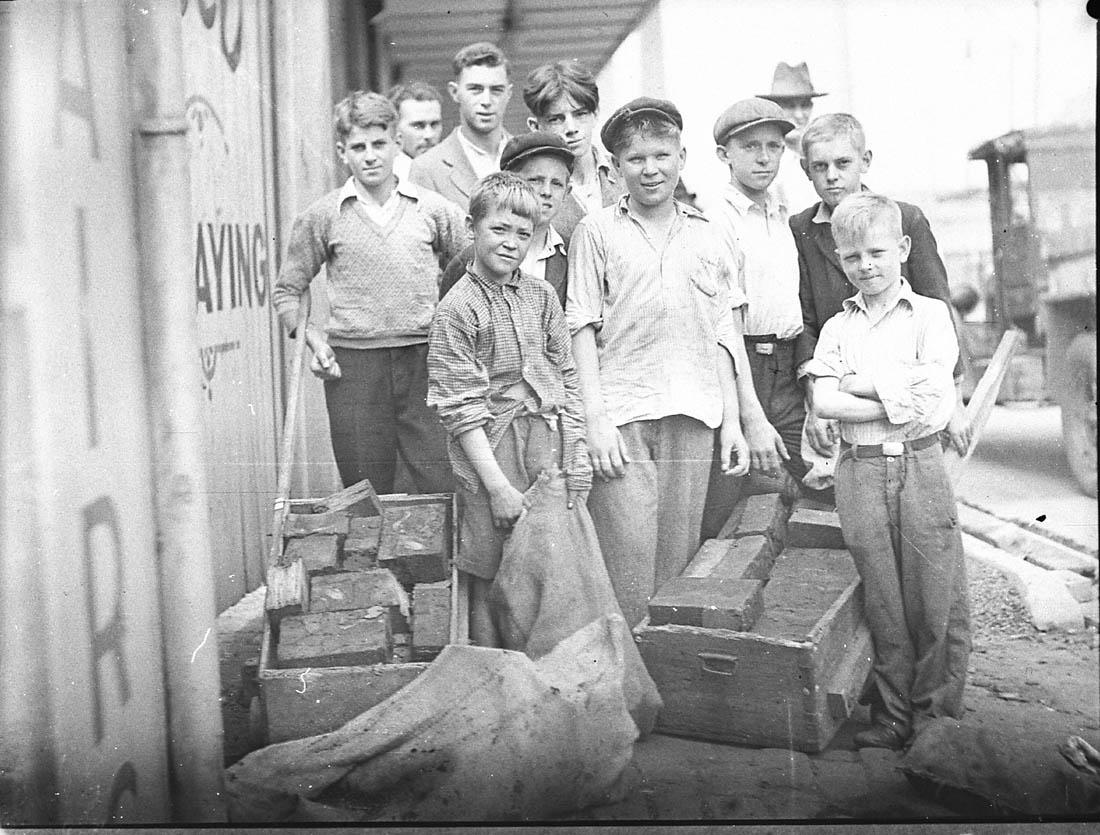

Who could not like this picture of a bunch of cheeky boys lined up for the camera with their hessian bags and billycarts full of wooden blocks? In the old days, carts like these were a necessary accompaniment to a boy’s life. Descendants of goat carts (hence the name ‘billy’ cart), these long-handled boxes on wheels were used for family errands and newspaper runs, and for hauling around whatever it was that boys liked to haul around.

The photograph was taken in April 1935 and a digitised copy of it can be found in the State Library’s Sam Hood ‘Home and Away’ collection. It has a title that I’ve always thought puzzling: ‘Block boys at St Peters’. Sam Hood was a commercial photographer, already successful when he opened a studio in Sydney’s Pitt Street in 1918, expanding his business from portraits and weddings to press photography and, later, advertising. Some years after his death in 1953, the Library purchased a huge collection of the studio’s photographic negatives from Hood’s family. Now digitised and publicly accessible, the ‘Home and Away’ collection is an astounding record of people, places, events and everyday life in Sydney during the first half of the twentieth century. It is exciting to learn that an even larger collection of Hood’s photo prints and negatives, purchased by the Library more recently, is currently being digitised.

I came across the billycart picture some years ago while pursuing my interest in roads and pavements. I was dubious about the title ‘Block boys’ because I knew this term referred to the youths who were once employed to sweep Sydney’s streets. The picture is popular and has been reproduced on history websites and Facebook pages; most repeat the misleading ‘Block boys’ title. Several years ago I even discovered that the décor at The Henson pub at Marrickville, in a nod to local history, includes a beautifully framed blow-up of the picture. It has a label stating that the boys ‘are helping to build roads using a method called woodblocking’. Interesting, but not true. It turns out that even though the real story is just as interesting, it does not carry connotations of illegal child labour.

As an occasional volunteer cataloguer of a local history collection, I know how difficult and time-consuming it can be to write a meaningful explanation of an unidentified photograph. Possibly there are clues about when it was taken and where, and something in the picture might give a hint about what’s going on. It’s enormously rewarding to unlock the key to a photograph’s story, but it’s also easy to misinterpret the clues. I am quite sure that even professional curators and cataloguers experience similar difficulties, so I am careful when poring through image databases for my own research and keep in mind that catalogue indexes can’t always be believed.

The images in the ‘Home and Away’ collection were each researched and indexed individually by Library staff, with the help of surviving studio registers and the assistance of Sam Hood’s photographer son, Ted Hood. It must have been an enormous project. But when the boys and billycarts photograph was being named, I think the stumbling block may have been the woodblocks themselves. Somewhere along the line, the concepts of ‘block’ and ‘block boys’ and ‘woodblocking’ were elided and these kids were saddled with occupations they didn’t actually have.

Looking for confirmation of my misgivings, I searched Australian newspapers, a task made possible by the National Library of Australia’s wonderful Trove database. Sam Hood worked as a freelance press photographer for several newspapers and I found what I was looking for in the Labor Daily of 4 April 1935. On page 8, this very picture is reproduced under the heading ‘Its An Ill Wind——’ with this caption:

Cement is replacing wood blocks on Cook’s River Road, near St. Peters station, and the boys of the neighbourhood took advantage of the occasion to collect cartloads of fuel for the winter.

Bingo! The boys are not constructing a road. On the contrary, they have been hanging about while the road is broken up so they can collect the discarded woodblocks and cart them home. Incidentally, that thoroughfare in St Peters is no longer called Cook’s River Road but is now part of the Princes Highway running south from Sydney.

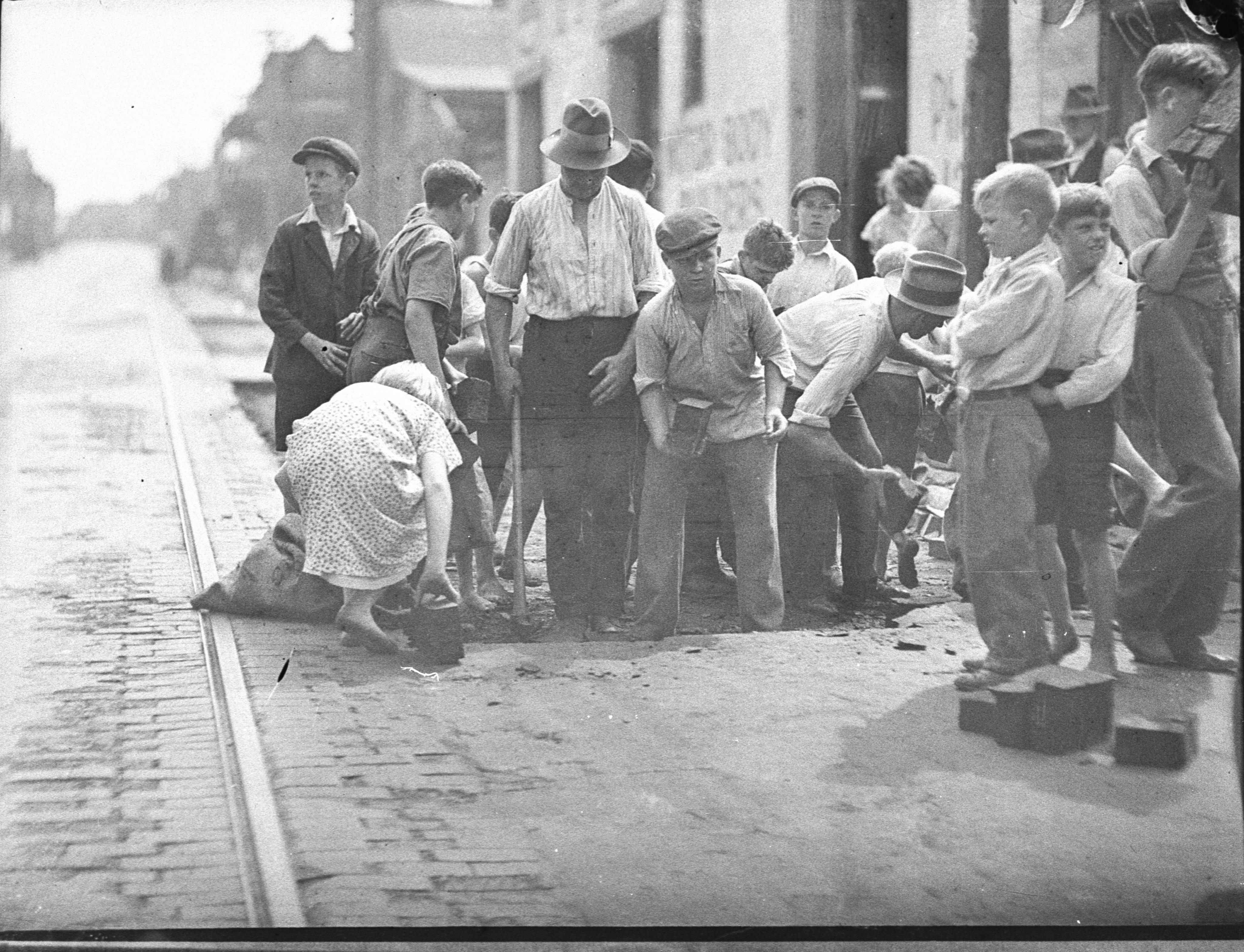

Woodblocks were once the preferred material for paving the streets of Sydney. Until the late 1800s, roadways were generally unsealed but the 1890s saw woodblocking come into widespread use by municipal councils. Hardwood blocks steeped in tar were laid like bricks, hammered close together and top-dressed with more tar. By the 1920s, this method of road building was no longer used and councils started ripping up the worn woodblocks and replacing them with asphalt or concrete, often in large-scale Depression-era programs that provided employment for out-of-work men. The project went on for well over a decade. Those tar-impregnated woodblocks would have burnt well and they were prized by householders as free fuel for fires and stoves. The Sam Hood picture was taken during the hard times of the 1930s and the local boys are contributing to their families’ wellbeing in a practical way.

There are several other photographs in the Library’s collection that were taken by Hood on the same day. Even though there has probably been some staging for the camera, these give a clearer idea of what is going on — workmen with pickaxes are prising up woodblocks from the road beside thetramlines; a cluster of boys, and a girl as well, are milling about ready to purloin them. No doubt similar scenes played outwherever woodblocked streets in the city or suburbs were being rebuilt.

So who were the real block boys? From the late 1800s, the City of Sydney employed a small army of youths to sweep up the tonnes of manure deposited by horses on the city’s streets. Officially known as ‘block boys’ because each was assigned to a city block, they were also jokingly called ‘sparrow starvers’. But by the early 1930s, the coveted job of block boy had been phased out. Motorised vehicles outnumbered horse-drawn vehicles and it became unsafe for youths darting in and out of traffic with their brooms and wheeled scoops. Of course there was less manure to clean up too, so street cleansing was subsumed into the more generalised duties of the council’s other outdoor workers.

Streetscapes all over Sydney were changing during the 1920s and 1930s as roadways — and the vehicles that drove on them — changed. In the heart of the city the once-familiar patrols of block boys began to disappear, while ragtag troops of boys with billycarts and gunny sacks stood by to grab the woodblocks that the block boys might once have swept.

Megan Hicks researches and writes about public space with a particular interest in paved roadways and footpaths and the stories embedded in them.

This story appears in Openbook summer 2022.