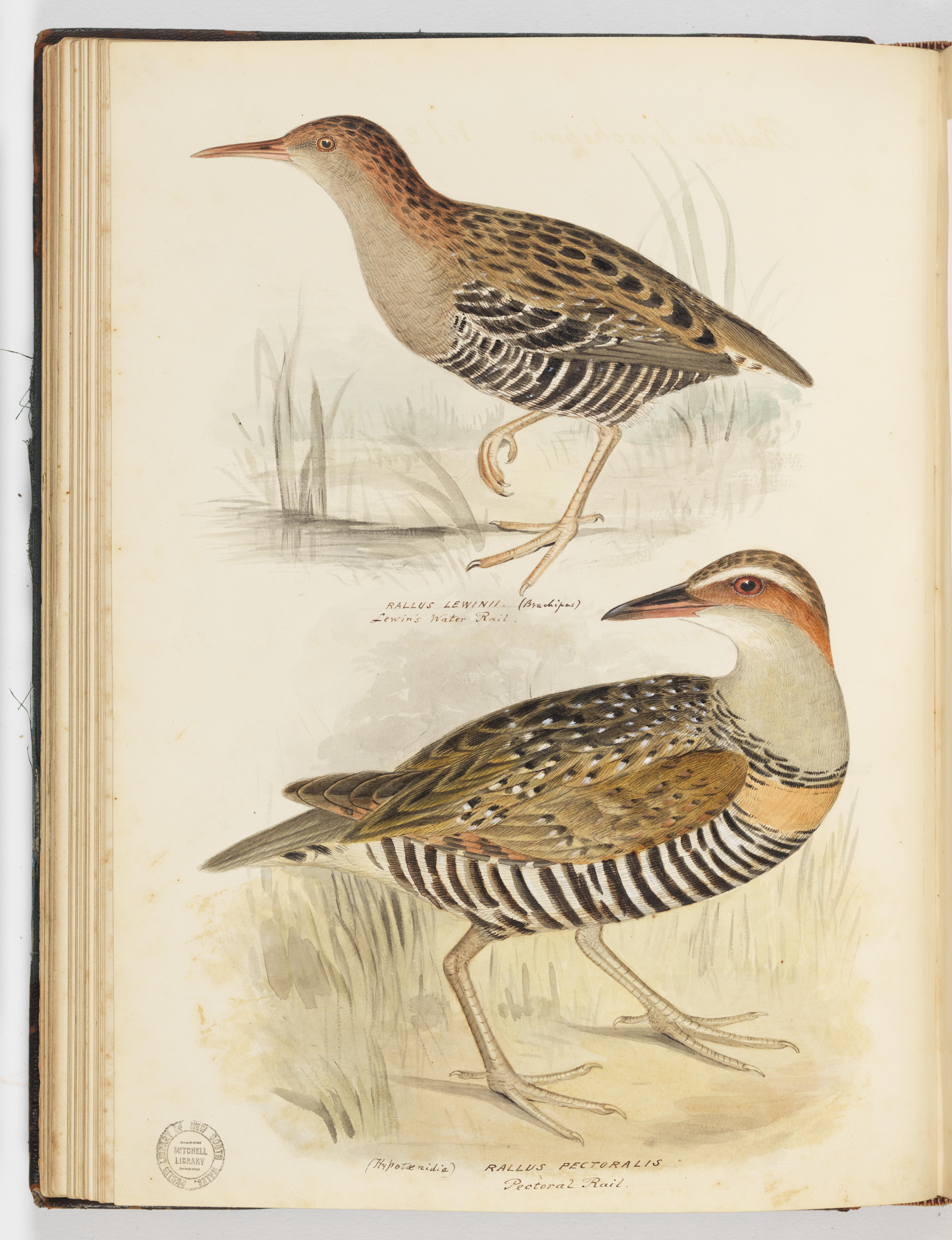

The Lewin’s Rail is a small, shy and secretive wetland bird. It is the colour of milk chocolate, aniseed humbugs and Jaffas. It has a range of peculiar calls: one sounds like a growling fox terrier; another reminds me of a galloping stallion. According to an older birding veteran I know, the Lewin’s Rail is possibly our most difficult wetland bird to see. Typically, you might get a five-second glimpse of the bird dashing between tussocks and reeds.

At Sydney Park, a 41-hectare oasis 6 km south of Sydney’s CBD, wedged between St Peters, Erskineville and Alexandria, I have been lucky enough to see this uncommon bird on many occasions. I have had sustained views of individual Rails foraging, calling and flying, as well as a pair mating — a four-second feat — and preening one another. I have seen a chick, reminiscent of an animated black-ink blot, skulking in the half-light at the base of reeds. I have even got to the stage where some birds respond to my clunky imitations of their calls. (Unsurprisingly, I do this when other people aren’t around!) This is all remarkable. I feel privileged to have developed such a connection with the species.

The Lewin’s Rail is one of 107 bird species I have now recorded at Sydney Park. This figure is roughly one-eighth of Australia’s entire number of bird species. According to the online birding database eBird Australia, no other birder has seen as many birds there as I have. Since people began birding in Sydney Park in 1998, 135 species have been recorded. This is an impressive tally for a re-wilded place that was formerly the site of a brickworks and a municipal waste tip. It was converted into a park with treed areas and wetlands in 2000. I have no doubt that the Gadigal People, the original inhabitants of the area, would have been aware of many more species prior to the arrival of white people.

Thanks to the efforts of all those who had a vision for a better planet, Sydney Park is now a thriving ecosystem with a network of ponds and bioretention swales that hold recycled stormwater. Water levels are controlled so that natural flooding and drying cycles can be replicated. There is a range of flora surrounding these ponds, including swamp banksias, coastal wattles, kangaroo grasses, king ferns, rushes and sedges. Long-necked turtles breed in the waterways and sunbathe on fallen logs. Common eastern froglets, Peron’s tree frogs and eastern sedge-frogs call through the warmer months. Brushtail and ringtail possums nest and forage in the gum coppices close to the ponds.

Sydney Park is encircled by roadways, heavy industry, commercial buildings, apartment blocks and the WestConnex motorway. It is a much-loved spot for young families, dog walkers, picnickers, joggers, skaters and kids learning to ride on the Park’s bike track. Running events are often held there. Dub–reggae enthusiasts and punk rockers turn up for specialist music nights by the Park’s old chimneys, a remnant from the old brickworks. There’s even an annual event celebrating Kate Bush’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ that takes place on the Park’s main hill, where red-clad devotees dance.

Perhaps Sydney Park doesn’t exactly scream birding mecca. Repeated visits to the Park — and great patience — have proven worthwhile though. I have become addicted to unearthing as many bird species there as possible. I’m not sure why, really. When I look at this objectively, it seems peculiar — when you think about it, choosing to count birds seems surreal.

Australia’s natural world, and birding in particular, has been my passion since 1985, when I received a hardback edition of Simpson & Day’s Fieldguide to the Birds of Australia from my grandparents. It led me to explore the wet sclerophyll forests of the NSW Central Coast, crossing my fingers for Regent bowerbirds, green catbirds and brown cuckoo-doves. I guess most men my age watch the footy, rewatch Game of Thrones or visit Bunnings ritualistically so they have a project in their shed to pour themselves into. I chase birds with a brand-new pair of 10 x 40 Nikon Prostaff binoculars. (My last pair of bins broke earlier this year when they fell off the roof of my Skoda and shattered while I was searching for emus near Belanglo State Forest.)

It is pleasing to see younger birders at Sydney Park, many in their 20s and early 30s. I have been inspired by their passion and their urgency to document and conserve. They have pointed birds out to me; I have guided them to birds they wanted to find. Sydney Bird Club, a Sydney-based group established in 2016 with some 500 members who are mainly in their mid-30s, recently had a walk in the Park that attracted dozens of people. When I began birding seriously way back in 1986, and became a member of the Cumberland Bird Observers Club, based in Sydney’s Castle Hill, the average age of members was much older but over time, birding has attracted younger people. Perhaps this is as we are all more affected by the perils of the Anthropocene.

My birding obsession is driven by curiosity, wonderment and an endless thirst for discovery. It is an obsession that will never be understood or appreciated by most Australians who see the hobby not only as weird, uncool and boring but, ultimately, as incomprehensible. About 10 years ago, when I was living in the NSW Southern Highlands, an elderly woman came up to me while I was watching a group of hardheads, or white-eyed ducks, at Bundanoon’s Wastewater Treatment Plant. She asked me whether I was a birdwatcher. When I replied that I was, she exclaimed, ‘Good for you!’. She then dashed off into a grove of scribbly gums, avoiding any further conversation. Perhaps odd, and even amusing, but it made sense to me.

I love what British nature writer Stephen Moss says in his birding memoir, This Birding Life, about the importance of a local birding area. ‘If you have a local patch — a place where you regularly go to watch and enjoy wildlife — then you are in touch with the passing of the seasons … In a world where it is all too easy to get things out of context, this is by far the best way to re-engage with reality.’ Moss is right, as Zen as it sounds, when he says reengaging with reality brings the moment into sharp focus. Birding at Sydney Park, my own local patch, does make me focus; I can escape the quotidian, or whatever has been dominating my thoughts. When I’m trying to identify a bird of prey, after a troop of stroppy noisy miners have sounded their raptor alarm shrieks, I’m not wondering whether I’ve been a good father lately or whether I’m teaching my Year 12 students the poetry of TS Eliot with aplomb, or whether North Korean missiles will land on Hokkaido and set off a catastrophic chain of events, or whether Ryan Gosling will be good as Ken in the new Barbie film. When I bird, I think only of the bird, all the bird represents and all it may become.

Here are some noteworthy moments from the last few years of birding at Sydney Park: Watching an iconic Australian ibis sail over the Park’s southern edge with a toilet roll in its beak, which happened not long before we all began fighting over toilet rolls during lockdown. Having a heated argument with an amateur wildlife photographer about the ethics of him entering a wetland to flush a rare Little Bittern so he could get a better picture of it. Watching a trio of peregrine falcons dash towards the CBD on a dazzling mid-February afternoon. Observing an eel snatch a dusky moorhen chick from the water’s surface and also noticing how this left a child upset. Being sized up by an adult Powerful Owl in the most densely vegetated part of the Park, its head bobbing, its enormous lemon jelly-yellow eyes looking at me as it clutched a dead ringtail possum. (I didn’t outstay my welcome — they can be dangerous during the nesting season. A forestry worker in Victoria once lost his eye to one!) Witnessing a yellow-tailed black cockatoo rip open a gum’s trunk with its beak to prise out grubs that had been invisible up to that point. Nearly breaking my neck to zoom in on the sky’s gleaming zenith, where 100 white-throated needletails, just back from Siberia, drifted and floated in a midsummer thermal, along with rising prayers, lost angels.

When I was last at Sydney Park, there was no sign of Lewin’s Rails. I played a recording of their call and made some imitations, to no avail. In one section of the wetlands, a huge white cat with yellow eyes froze and stared at me. I scared it off. In late 2022, another cat, this time a ginger tabby, was prowling through the wetlands. I threw a large rock at it. Unscathed, it ran off.

Around that time, on a Sydney Park Facebook page someone made a comment about what a menace cats in the wetlands were. The number of people who jumped on the page to defend the cats’ welfare and natural survival instincts was astounding. They seemed oblivious to the threat cats pose to our birdlife. Just as I was finishing this piece, I listened to a Radio National podcast that centred on the impact of roaming domestic cats. In an Australian National University study conducted for the Biodiversity Council, the Invasive Species Council and Birdlife Australia, researchers found that roaming domestic cats kill 546 million animals per year, 60 per cent of them native to Australia and many of them birds. In urban areas across the country, there are 50 to 100 cats per square kilometre!

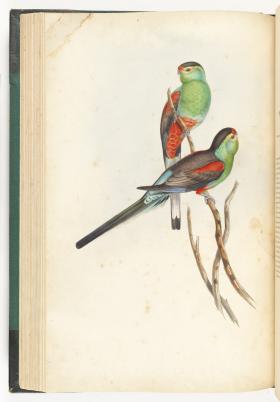

In September 2022, some birding mates and I visited Scotia Sanctuary in far-western NSW, a 600-square kilometre nature reserve of dunes, swales and mallee. The Sanctuary is looked after by Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC). We were hoping for a glimpse of the scarlet-chested parrot, one of the rarest and most nomadic of Australia’s parrots. Sadly, we didn’t see one. Scotia Sanctuary has a predator-free section, home to rare mammals such as bilbies, numbats and bridled nail-tail wallabies, relocated from other areas of Australia. The AWC crew at Scotia are on a mission to keep cats out of this safe space. There are daily patrols of the enclosure fence when staff look out for any new openings. Feral cat cages, complete with hanging, glittering tassels used as lures, are placed along the fence line. I think a lot more could be done to monitor the cats at Sydney Park. It’s a task for the Park management, but local residents need to do more to keep their cats indoors too. Otherwise, cats at Sydney Park could kill off the Lewin’s Rails and most of the smaller waterbirds there.

There are other threats: foxes, rats, eels, off-leash dogs bounding into the ponds, water quality, spreading fireweed, extreme heat conditions — and everything else the Anthropocene hands us — are putting enormous pressure on Sydney Park’s birds. And the threat of development looms: green spaces to the south of Sydney Park at Tempe and Banksia have been destroyed, or dramatically altered, for roadways and various redevelopments.

Birdlife Australia is the premier conservation organisation for Australia’s birds. Its website says that too many of our birds are in trouble. Indeed, some species are at crisis point and more have been added to the threatened species list for Australia. Migratory shorebirds and dry woodland birds are particularly vulnerable right now. The news seems bleak. Still, I carry hope in my heart. Just. I will continue to monitor, record, admire and celebrate the birdlife of Sydney Park. And fight for it.

Naturalist and historian of science, Helen Macdonald sums up the feeling of connecting with wild birds in her essay ‘What Animals Taught Me about Being Human’. When a rook notices her briefly, she writes, ‘And with that glance I feel a prickling in my skin that runs down my spine, my sense of place shifts, and the world is enlarged.’ Maybe, sometime, I’ll see you by the wetlands of Sydney Park, new binoculars around your neck, listening for the fox-terrier-and-galloping-horse sounds of Lewin’s Rails, very glad you decided to get out of your spinning head for a while and return to the natural world’s reaching arms.

Lorne Johnson lives in Newtown and teaches at Ascham School. A widely published poet, Lorne released his collection Morton in 2016. His poem ‘An assessment on The Tempest’ appeared in the Summer 2022 issue of Openbook.

This story appears in Openbook spring 2023.