It’s the middle of summer and roasting hot when I drive down a bumpy dirt road in Wedderburn, my tyres spitting tiny bits of rock into the dusty verges. I’ve come via Campbelltown and driven through a semi-rural area where the orchards are wearing bridal veils of white netting to keep the birds away.

I’ve crossed a wooden bridge and entered dense bushland. Now I’m pulling up at a small wattle and daub house on a bushy slope below the road. Outside the car, the cicadas are going full blast. The landscape has that crackly, dusty smell that comes with a long dry spell.

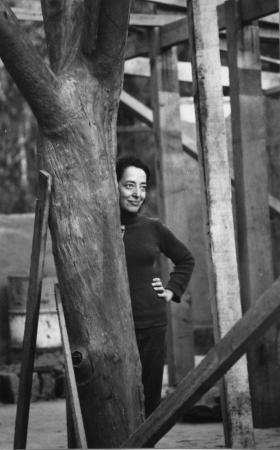

Elisabeth Cummings is standing out the front of the little house waiting for me, probably glad I found my way. She looks cool, dressed in a t-shirt and linen trousers.

I offer her my city-bought gerberas and she hurries to find a vase before they droop in the heat. For a moment, she’s lost in her enjoyment of the rich red and orange of the flowers. She points out how beautiful they are underneath, where the bright petals meet the juicy green of the stems.

Looking at flowers from underneath is not something most people do. But Cummings has a unique way of seeing the world. Her paintings are not faithful depictions of reality. But they’re not completely abstract, either. They hover in between, with intriguing shapes that keep you coming back to look again while your brain tries to reassemble the image into something it can recognise.

At the same time, you’re conscious of not really caring what the picture depicts because you’re getting such a charge from the lush colour combinations, the bold forms, the tiny patches of striping, and the lines drawn with the wrong end of a brush dragged through wet paint.

Cummings’ paintings have been compared to poetry, where so much emotion is implied or suggested, rather than spelt out. Interestingly, she adores poetry and copies her favourite pieces into a special book. Among her best-loved poets are Judith Wright, Les Murray, Roy Campbell, John Clare, WS Merwin and Gerard Manly Hopkins.

Given her long exhibition career, not to mention three decades of teaching young artists, it’s wonderfully fitting that Elisabeth Cummings is being celebrated at two important Sydney art institutions this year.

Now the NAS Gallery, on the National Art School campus in Darlinghurst, has mounted a survey show from the last 30 years of her painting practice. Radiance: The Art of Elisabeth Cummings is on from 18 August until 21 October 2023.

Cummings graduated from the National Art School in 1957, when it was East Sydney Technical College. When she returned to Sydney after a decade in Europe, she taught at NAS from 1969 to 2001. (From 1975 to 1987, she also taught part- time at City Art Institute, which became COFA and is now the UNSW School of Art and Design.)

It was ‘an enormous pleasure’ to bring Cummings’ work back to her alma mater, NAS director and CEO Steven Alderton said. ‘Since leaving art school, she has determinedly and daringly painted her way to the stature of one of Australia’s most eminent artists. Her practice is a deeply intuitive process, steeped in memory and her connection to the Australian landscape, beginning in her Queensland childhood.’ He adds, ‘She’s an inspiration to our students today.’

The exhibition, curated by Vivienne Webb, includes more than 50 paintings — interiors, landscapes and even some gouaches completed en plein air. To deepen the impact of the exhibition, NAS has published a new book about Cummings’ art.

Campbelltown Arts Centre also celebrated Cummings’ huge contribution in an exhibition that closed in August. The artist was already living in Wedderburn in 1988 when C-A-C opened nearby under its first director, Sioux Garside.

Elisabeth Cummings: From a Well Deep Within, curated by Emily Rolfe, focused on Cummings’ printmaking with 48 artworks, including etchings and monotypes produced in partnership with distinguished printmakers Michael Kempson of Cicada Press and Diana Davidson of Whaling Road Studio. Excitingly, three forgotten etching plates were rediscovered this year by artist Luke Sciberras when he was helping out in Cummings’ studio. Cummings and Kempson took new prints from these plates for the C-A-C exhibition.

The year after Cummings graduated from NAS, she went to Europe on a scholarship and settled in Florence for 10 years, where she painted and taught English. The city became a base for wide-ranging travels and was also where she married fellow artist James Barker in a civil ceremony in the Palazzo Vecchio, just across the square from the Uffizi. ‘We got married by a little fat Italian man with an Italian flag wrapped around his middle,’ Cummings said. Their son Damian was born soon after.

Curator Sioux Garside has written that Cummings went to Wedderburn wanting to ‘reconnect with the Australian psyche and landscape after living for 10 years in Florence, immersed in the art of the classical world and early Renaissance art’.

In time, Cummings had a small, simple home designed for the location, built from local clay, and wattle and daub. It’s outside this house that Cummings waved to me in January 2021.

Even though I’m an arts journalist, I had never done a proper interview with Cummings. I badly wanted to fill that gap, and I reached out through King Street Gallery on William, her long-term representative.

Ever gracious, even making a superb lunch for us to share, Cummings welcomed me and gave me a precious glimpse into her life at Wedderburn. I wrote in my diary that night: ‘As you look at it from where you park, the house is in two distinct parts. On the right is the wattle and daub section that was built for Elisabeth in the 1970s. On the left, separated from the other part of the house by the breezeway, is a little dwelling area designed for Elisabeth by her architect son Damian Barker.

‘Through the breezeway you could see a hillside of quite sparse bushland on the other side, with lots of beautiful big rocks. If you walk through the breezeway to the other side of the house, and hop down onto the ground, you can walk a few steps through the rocky bush and look down into the gully below. It was completely dry there, although it runs when it rains. Elisabeth told me they were desperate for some rain.

‘The structure on the right-hand side is really just one big room with a double-sided fireplace dividing the spaces, and a smooth tree-trunk poking straight through the wooden floor and up to the ceiling.

‘There were many little windows and French doors set into the mud walls at lovely angles so you could see the bushy hill opposite,’ I wrote. ‘There were also a few funny little windows, no bigger than your palm, set deeply into the walls with amber-coloured glass. A bank of dormer windows ran along the top of the wall, letting in lots of light. A section of woven wattle branches had been left without daub, to show what the interior structure of the walls looks like.’

The tiny kitchen has a wood-fired stove with a wood box on one side. It was here one hot and windy summer’s day around 10 years previously that Cummings was visited by an unwelcome guest. A deadly king brown snake had come in, probably seeking water in the drought, and had draped itself around the kitchen sink.

Thinking quickly, Cummings put her dogs in another room and called WIRES. But there was no need. The snake had gone. ‘I think it eventually went out the way it came in,’ Cummings said. ‘I’ve seen other browns, but not a big one like that.’

The house is on tank water, which can be quite discoloured. For this reason, Cummings brings drinking water up to Wedderburn from her other home in Balmain. She wiped down our lunch plates so not a skerrick remained on them. She didn’t want anything foreign to go into the drain and thence into the landscape.

A conservationist, Cummings has taken part in campaigns against fracking and mining in the area. She adores living so close to wild animals. Even spiders, which don’t seem to trouble her.

During lunch, a tiny bush rat called an antechinus scurried across the top of the open door and along the inside wall. Committed chewers, they mercifully don’t have a taste for art. ‘They’re very pretty’, but they can take over,’ Cummings said. ‘I catch them occasionally and just take them up to the far reaches of Wedderburn, but I’m sure they run back.’

Cummings often sees wallabies in little groups on the rocks outside. One day her granddaughter, Ivry, was drawing on the verandah when a koala ambled past. Such sightings cause great excitement in the Wedderburn artist colony.

As a child, Cummings started art lessons with the distinguished Australian artist Vida Lahey. Later, she was a student of Margaret Cilento whose sister Diane would marry (and divorce) the actor Sean Connery. Margaret Cilento, who Cummings remembers as a gentle spirit, had been a student at the National Art School and said to Cummings: ‘You should go.’

‘She had bright red hair,’ Cummings said. ‘I was very delighted with her eccentricities. She wore different shoes — pretty little shoes, but they were from different pairs. Because she had lived in New York and Paris and London, she had good stories. So that’s when I thought I’d be a painter.’

Lunch was over and we’d talked for hours. I got back in the car, dying to get back home and start writing it all up. ‘I drove up Elisabeth’s steep, bumpy driveway with a great slippage of tyres and scattering of stones,’ I wrote later.

Looking back towards the house, I could see Cummings standing quietly at her door and waving.

Elizabeth Fortescue is a freelance arts journalist. She wrote about Peter Kingston in Openbook Autumn 2023 and about Cressida Campbell in Openbook Spring 2022.

Radiance: The Art of Elisabeth Cummings runs at the National Art School in Darlinghurst until 21 October.

This story appears in Openbook spring 2023.