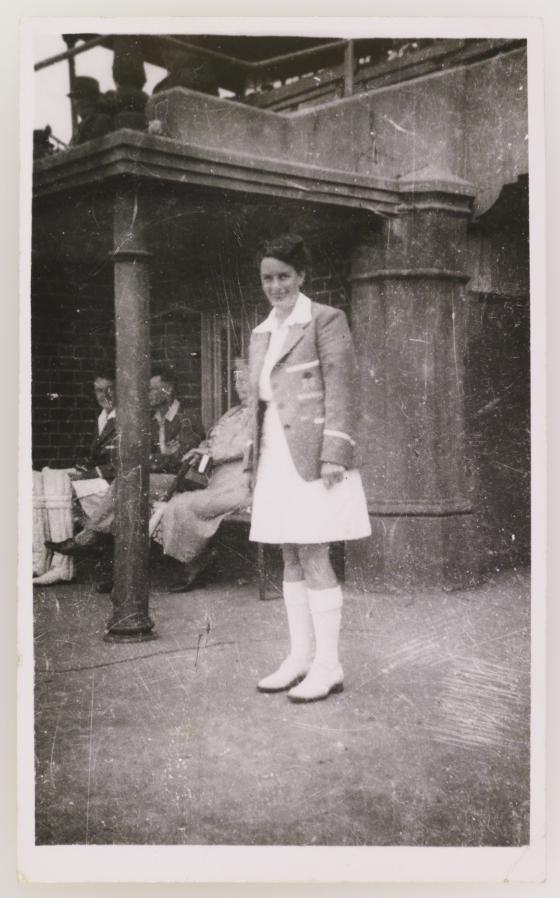

What pride Lorna Thomas must have felt when she opened the newspaper one day in November 1941 and read the headline ‘Lorna Lays Down the Law’ in the women’s sport section. Playing for Balmain, an inner west suburb of Sydney, she had taken seven wickets for just five runs in a dominant victory over the Board of Study team. Lorna had grown up in the area and started playing cricket in the late 1920s. She was skilled enough to represent New South Wales from 1937 to 1950, though she never quite managed to make it into the national team.

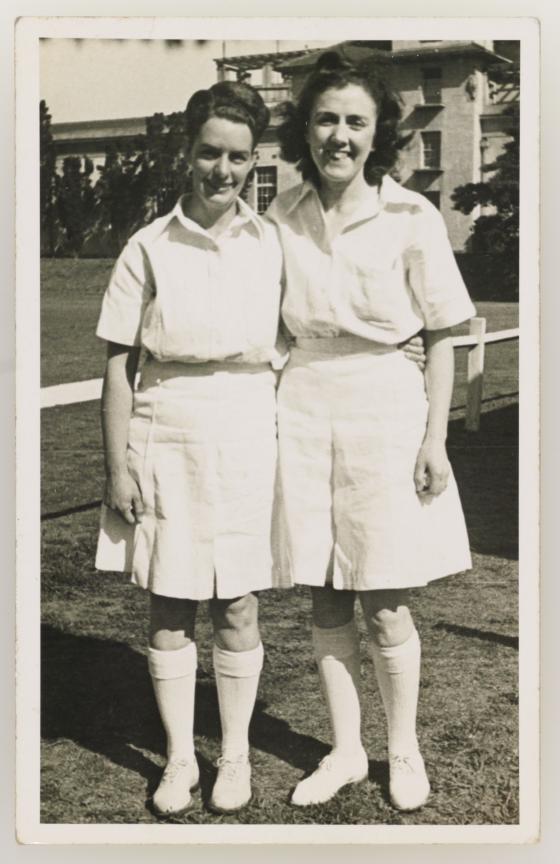

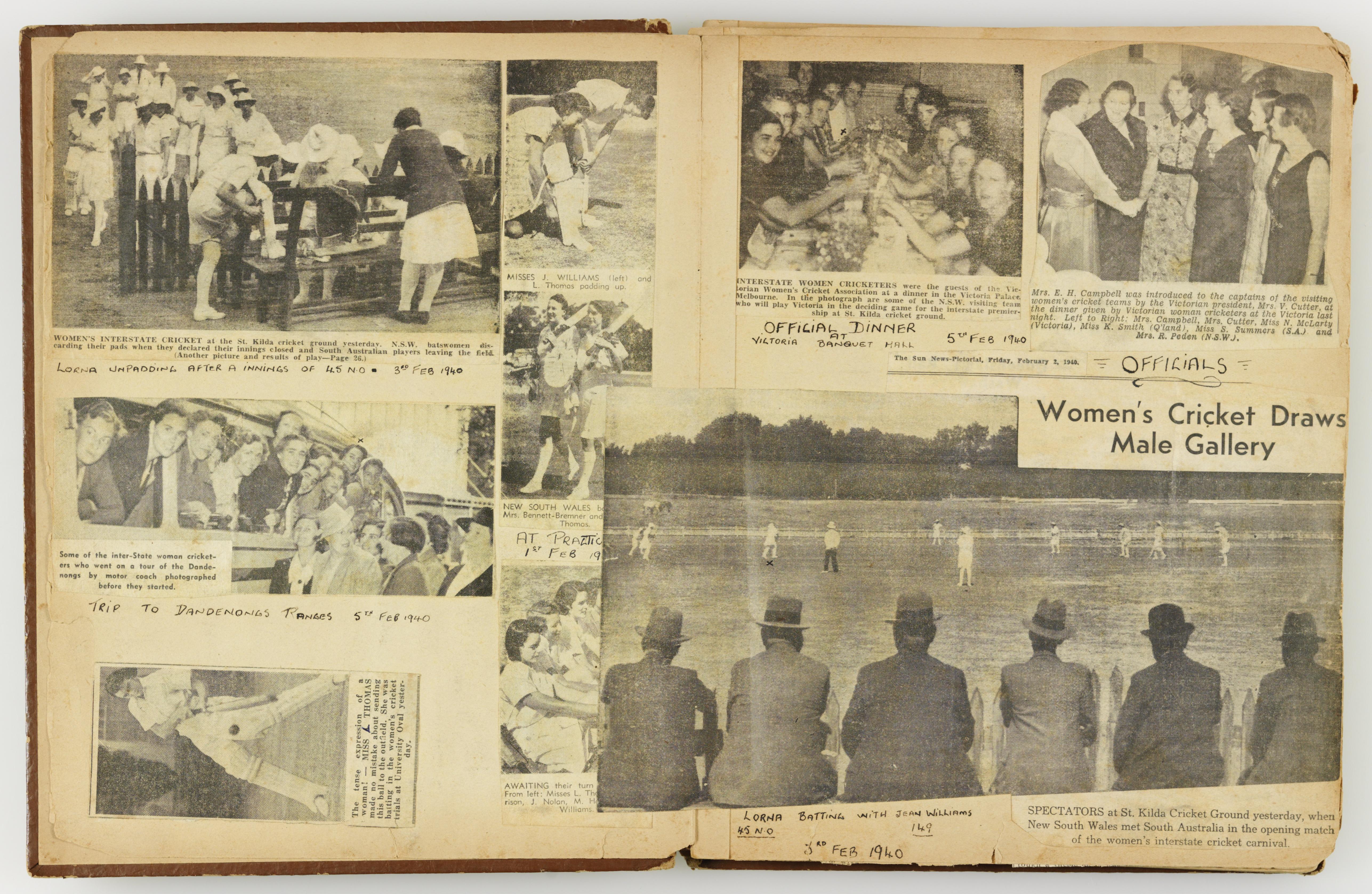

Clearly the article meant a lot to Lorna — she kept it in a scrapbook for the rest of her life. It’s just one item among many in the State Library’s Lorna Thomas collection. Over the course of her life, Lorna collected like a magpie: stuffed inside three capacious cardboard boxes are hundreds of photographs, thousands of press cuttings, a diary of an overseas tour, correspondence, programs, and invitations to many events and receptions.

If anyone thinks that women’s cricket in Australia is a recent phenomenon, send them here. This rich and varied archive chronicles the deep history of the women’s game in Australia and around the world.

This history began in Bendigo, where the first recorded women’s cricket match in Australia was held in 1874. The first interstate game, played between NSW and Victoria, came in 1891 at the Sydney Cricket Ground.

Among the pioneering figures were the Gregory sisters, Nellie and Louisa, who played a major role in the game’s growth in New South Wales. Both sisters captained sides up to state level and organised matches; Nellie even taught cricket to girls in schools. In 1927 she became the first President of the NSW Women’s Cricket Association.

Then, in 1930, came the Australian Women’s Cricket Council, co-founded by Margaret Peden, who became the dominant force in the development of the women’s game in Australia. Peden was Australia’s first Test captain, held almost every post in the administrative setup at one time or another, and organised the first England women’s tour of Australia in 1934.

She also captained NSW from 1930 to 1938, and it was under her leadership that Lorna made her debut for the team. Women like Peden inspired Lorna to devote much of her life to the game she loved.

When Lorna’s playing career eventually ended in 1950, she focused on the administrative side and eventually became Vice President of the NSW Women’s Cricket Association for 20 years from 1960 and President of the Australian Women’s Cricket Council from 1967 to 1969. She was becoming to her generation what Margaret Peden and Nellie Gregory had been to theirs.

Lorna’s most significant role was as manager of the Australian women’s team on four overseas tours between 1960 and 1976. These tours helped to establish a regular overseas schedule for the team, but they were not without their challenges: principally the difficulty of gaining recognition for the women’s game and, predictably, raising funds.

During the 1963 tour of England, which Lorna oversaw, the players voiced these issues in the press. Player Hazel Buck told the Birmingham Post that ‘we are not so much resented as ignored’ in Australia, despite the game’s deep roots back home. ‘Australian men’, the article continued, ‘made unfair and totally wrong comments about “thick legs” and “Amazons.” Cricket, they said, “is not the game for women”.’ Physical appearance had long been used to describe women’s cricket in the papers.

It was a frustration that Lorna was all too familiar with. In one of her scrapbooks she kept an insulting cartoon from her playing days which poked fun at the NSW women’s contest against the touring England team in December 1948. The players, referred to as ‘cricket-hers’, are depicted taking more interest in their makeup and glamorous outfits than in the game itself — the cartoon jokes that ‘a girl might get caught in the slips’ (referring to the garment rather than the fielding position).

This lack of recognition for their application and skill must have been particularly galling given the sacrifices the team members made to join these tours. ‘All the team have paid their own fares,’ noted the 1963 team’s captain, Mary Allitt, ‘and have either given up their jobs or taken leave without pay. There are sales-girls, typists, sales managers and five teachers.’

Each member of the team — called ‘the “pay-your-way” women cricketers’ in one British newspaper — had to contribute around £700 (about $20,000 today) for the tour to go ahead — an astronomical sum for most of them, with various state cricket associations only covering a small percentage of the cost.

Some received donations to help with the expense, but many had to take on extra jobs. Patricia Thomson, who usually worked as an accounts clerk in Sydney, took on a job as a barmaid at night to pay for the trip.

Many of the members of these touring parties had never travelled abroad before. In her role as manager, Lorna acted as a kind of motherly figure, soon acquiring the nickname by which she was regularly referred to for the rest of her life: ‘Aunty Lorna’.

The tours offered the players the chance to compete against high-quality opposition, sightsee, socialise at the many functions held for them, and meet new friends abroad. ‘They’ve had such good Press notices that there are always crowds around them,’ one British paper reported in 1963. Lorna noted in her official report of the 1963 tour that there were ‘frequent visits to cathedrals, castles and tours of the countryside. Many Mayors entertained the team … [and there were] functions as diverse as tea at the House of Commons.’ During the 1976 tour of England, Lorna even received a card from then Leader of the Opposition and later Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, inviting her for tea at the Palace of Westminster.

Lorna must have been particularly heartened when she received a letter in July 1963 from an Englishman who had attended one of their games at the Oval in London. Describing himself as a new-found ‘fan’ of the team, he noted with a touch of condescension that ‘never having seen ladies play real cricket before, your young ladies amazed me by their skill and keenness on the field … I don’t know when a ladies team is to visit our old Island next but I shall be there if I go to the ground on a pair of crutches.’

Women had, of course, been playing real cricket in England for some time: the first recorded match had taken place at Gosden Common in Surrey in 1745, and women’s county cricket had been a feature since the early 1930s.

But this kind of praise mattered to Lorna. Indeed, in her report of the 1973 tour of England and Jamaica, she wrote that the ‘male followers of the game of cricket were most impressed and enthusiastic with the Australian Team’s performances, and in this capacity the team was accepted.’ Though the press stereotype of the ‘sun-bronzed girls’ continued to stalk the team, along with constant questions about its members’ marital status, there can be no doubt that the tours helped it to make a name for itself both at home and abroad.

The 1976 tour proved to be Lorna’s final with the national team. During her nearly three-decade long involvement, women’s cricket had made great advances. The inaugural women’s World Cup, for example, had been held in England in 1973, preceding the men’s competition by two years.

These advances and the importance of recording them help explain why Lorna collected on such an extraordinary scale. She felt the influence of her predecessors profoundly and sought to continue their work. As Lorna stood on the shoulders of those like Margaret Peden and Nellie Gregory, so too do the players of today stand on the shoulders of those like Lorna. As the women’s game continues to grow, we will continue to see the emergence of new characters who feel compelled to help the process along.

Daniel Seaton is a writer and PhD candidate in history at the University of Sydney. His writing has featured in publications like The Wisden Cricket Quarterly (known as The Nightwatchman), Overland and Australian Book Review.

This story appears in Openbook summer 2021.