Winnie Dunn is a writer of Tongan descent from Mt Druitt in Western Sydney. She is the General Manager of Sweatshop Literacy Movement and the editor of several critically acclaimed anthologies, most notably Sweatshop Women, which is Australia’s first and only publication produced entirely by women of colour. Her work has been published in the Sydney Review of Books, The Saturday Paper and many other publications. She is now working on her debut novel as the recipient of a CAL Ignite grant.

Winnie’s grandmother Losē Po‘uliva‘ati was born in Malapo, a small village in the eastern district of Tongatapu on the island of Tonga. Winnie came to the State Library to look at maps and books that show Tonga through the eyes of missionaries and other colonists. This glossary of tapu (taboo) terms is her response.

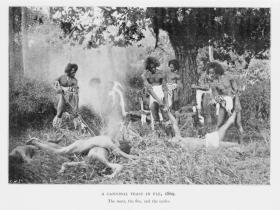

Cannibal

1. ‘Thus says the Lord God: Because they say to you, “You devour people, and you bereave your nation of children,” therefore you shall no longer devour people and no longer bereave your nation of children, declares the Lord God. And I will not let you hear anymore the reproach of the nations, and you shall no longer bear the disgrace of the peoples and no longer cause your nation to stumble, declares the Lord God.’ — Ezekiel 36:13-15

2. The English reproached us for consuming the flesh of our own. The English called it forbidden. Called us cannibal. Used this ancient act as a reason to have their blond-headed, blue-eyed Jesus destroy our Old Gods. But the more they taught us, the more we asked: Is your Jesus not a human sacrifice? Hasn’t the consumption of his flesh and the spilling of his blood saved you all from hell?

3. King Tu‘i Tonga was humbled by the couple Fevanga and Fefafa because they sacrificed their only daughter, Kava kilia mai Faa‘imata (a leper), as an offering to him. From her grave grew the first kava and sugar cane plants. Our King, Tu‘i Tonga, is a descendant from our original God. Kava for the king. Sugar for the peasants. See too how our human sacrifices save us?

4. When White people eat other humans, it is called colonisation.

Chapel

A four-walled room with a high ceiling and a door. We have never seen a structure like this before the palangi invaded. They erected these strange monuments on our lands, which moved heaven beyond our reach. This is to be expected for us savages. We have yet to earn their forgiveness.

Collection

How can I reclaim the stories written about my ancestors when they are kept in state-sanctioned private collections? Why does something written in the 1800s have more significance than the voices of my ancestors passed down to me?

Cocoanut

The only time the English couldn’t tell the difference between white flesh and brown flesh.

Feejee

Even when ancient Tongans enslaved ancient Fijians … stealing their person, their labour and their art … at least we knew their real names.

Fie palangi

In Tongan, we have a phrase for the phenomenon where people of colour want to be White.

Fonuamomoko

1. An infertile piece of land.

2. An infertile Tongan woman (e.g. Winnie Dunn).

Friendly Islands

Little did Cook know we were planning to spear him like ’ota (fish) when he sailed on too soon. Little did Cook know that the Hawaiians he invaded after us were ancient Tongans so, in a way, we still had the honour of killing him.

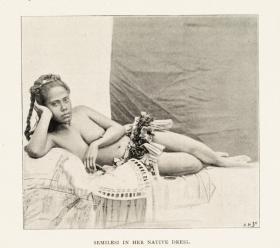

Gold escort

1. Any Pasifika woman who willingly dates a White man.

2. Any Pasifika man who willingly dates a White woman.

Heathen

The White man calls us this in all of his books. He does not know that he has made us this way.

Hina

Ancient goddess of the moon who moves saltwater and bathes in freshwater.

Horse

In Tongan, a fai hoosi is a horse fucker. This is what we became when we gave ourselves to a blond-headed, blue-eyed Jesus.

Implanon

I purposely made myself infertile. Every three years, Doctor Yu at Rooty Hill Medical and Dental Centre cuts open the inner-side of my upper left arm and inserts a small plastic rod that stops me from ovulating and sperm from invading my uterus. A Tongan woman is only meant to have sex for procreating. Never for pleasure. Yet, my Implanons have seen me through one-night stands, fourth-date sex in the back of cars and two long-term relationships that bled into each other like my infrequent period. Sometimes I wonder if what my people say is true. That the uterus is a piece of Tongan land meant to grow and pass on to the children I could carry inside of me. What does it mean now that I’ve made it barren?

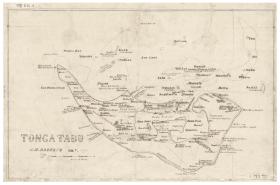

Map

The palangi think that drawing on paper means they can own the world.

Map-making

This is a process us Tongans know the best. We saw Maui’s hook in the sky and discovered how our original gods left marks there to show us the islands they fished for us from under the sea. The stars matched the patterns of our fingers and palms.

Maūi

An ancient demigod from the loins of Tangaloa, our original god. Maui pulled up our coral islands with a fish hook, threw coral boulders at birds that woke him up too early, and smeared the head of an eel on the trunk of a tree in order to feed us for eternity.

Missions

1. A holy way to subdue the natives.

2. Christianity was propagated to us by sexual means. Our legs were spread open so that the Holy Spirit could be transmitted to us. From our bodies grew chapels.

Native

1. In Tongan, there is no word for ‘native’ or ‘Indigenous’. The term ‘Tongan’ itself implies that I am of an original people from an original land in the South Pacific.

2. It was the White people that first differentiated themselves from us. Made their status higher than us purely through the use of language. What was White before them? What was Native before them?

Palangi / Papalangi

Our original coloniser.

Taboo

This is the English word I’m most proud of because it came from us. We created the term for what could not be done and what was forbidden. We formed the basis of our society by first outlining what we could not act upon and what we could never say. This outline was made out of respect for ourselves, for the land, for the spirits and for the gods. But I will say, the English spelling looks childish. Boo!

Tangaloa

Our original god.

Tapu

1. The original meaning, spelling and spirit of what is known today as ‘taboo’ in the English language. What we consider our tapu:

- whistling at night

- weeping at night

- brushing our hair at night

- cutting our hair (unless in mourning)

- weaving at night

- bathing at night

- bathing during our period

- eating cold foods during our period

- eating our father’s leftovers

- to lie down next to our brothers

- to sleep with our brothers in the same room

- to marry our brothers and sisters (we do not have a concept of ‘cousins’)

- to stand in the presence of King Tu‘i-tā-tui (lest we are caned at the knees)

- to touch our father’s head

- to reject the will of our father’s eldest sister (known as mehekitanga — a title bestowed only to women because only women can lead a family)

- to purposefully make one’s self infertile.

2. I struggle against my nana’s thick taro-like grip as she wrestles me into a kafu. ‘Fonuamomoko, fonuamomoko, fonuamomoko!’ she cries as my clenched left fist narrowly misses her jaw. The fluffy blanket with a printed pattern of purple peacocks, bought from Flemington markets, makes my breath shallow and my head sweaty. It is pulled tightly under my chin, across my throat like a noose. It is a Mt Druitt summer, where the temperature stays at 40 degrees even in the middle of the police-siren-filled night. Why was she so afraid of my womb getting cold?

3. My grandmother’s maiden name was Mapapalangi. Mapa meaning a tree with orange leaves or unlaid turtle eggs and palangi meaning white. My grandmother’s first name was Losē meaning rose in English. These days, I wonder if God created my grandmother for the White man who sought her out.

‘Daughta. I haf daughta for you mah brotha.’ This is what I imagine my great-uncle to have said to Brian Dunn as they worked on the railroads in Auckland. The only jobs around for Fobs and English/Irishmen back in the 60s. ‘Wife. I look for wife,’ I imagine Brian would say, mimicking my great-uncle’s broken English. A trait my father has to this day when he orders Chinese takeaway at Rooty Hill or Paradise Chicken in Mt Druitt. ‘Wife. Wife. My wife,’ Brian proclaimed when he saw my grandmother — light brown skin with freckles, big black afro and calves the full curve of a crescent moon. Maybe he had grown bored of his own women.

‘If you no marry, you no life.’ My grandmother’s mehekitanga warned. Nana sobbed about how she had a boyfriend back on the islands she had wanted to marry. How only Tongan men could pass on the rights to the fonua. ‘I Tonga. I Tonga,’ she repeated. My grandmother knew her life with Brian was an exodus. She knew her children, and her children’s children, would have no part of Tonga to claim besides the part inside her womb.

Her mehekitanga was firm. ‘You go. Australia. Be us there. New life. New life. Sīsū bless us.’

4. Tongans were subject to the White Australia policy unless they pretended to be Māori or they were married to a White man. My grandmother did both, just to be safe. By denying Tonga, she became a tapu woman on a foreign land.

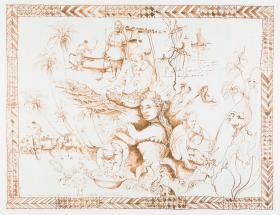

Tatau

The original meaning, spelling and spirit of what is known today as ‘tattoo’ in the English language. What we consider our tatau:

• Unknown. The ancient practice was eradicated and forgotten in Tonga due to Christian colonisation.

Tattoo

Every second cop standing at the ticket gates of Mt Druitt station has one protruding from underneath the blue sleeve of their uniform. With their tattooed arms they fine all the Fob boys that jump the train. What a shame job to our ancient practice.

Tongatabu

1. A colonial reimaging of Tonga.

2. ‘Just under the red of sunrise on the starboard bow, dimly through the glass, silhouetted against a pale, yellow-green sky, stand, as it were, right out of the ocean, the feathery tops of cocoanut trees, and nearer, puff! puff! puff! one after the another, stretching almost a mile along the horizon, like shells fired from a line of forts and exploding in the water, leap twenty feet into the air little heaps of white spray. These are the waves breaking over a line of coral rocks, and up through submarine caves in the rocks. The first impression I feel is certainly not a grand one to record.’ (Edward Reeves, Brown Men and Women, 1898, p 59).

Tongatapu

1. The main island of Tonga. It is ancient and unending.

2. Just under the blue of sea on the south, dimly through the clouds, silhouetted against a pale darkness, as it were, right out of the ocean, the feather tops of nui pulled nearer to the surface — tug! tug! tug! mass after mass. Stretching to the length of an ancient turtle, its sighs like volcanoes only Tangaloa and Pele can control, turning into exploding water, leaping in faka‘apa‘apa of salt and foam. This is Tangaloa blessing his half-human son to lift Tonga from its depths. The first impression I feel is a miracle of creation dangling from a hook. Certainly, a grand one to record.

Tulou

‘Too low! Too low!’ The missionaries complain when they invade our fale (house) where we have built the ceilings within our reach. We interpret this as a sign of deep respect. ‘Tulou, tulou,’ we respond. ‘Excuse us, excuse us.’ Such is the ultimate sign of respect, to excuse ourselves on our own land to invaders.

Wesleyan

1. A personalised branch of Christianity that Tongans use to subdue each other. How can we claim to be Christian if we do not refinance our home three or four times over to give money to God via the church? How can we claim to be Christian if we do not sit for four-hour long sermons in the Western Sydney heat? How can we claim to know God if we do not drag our nine children to church every Sunday?

2. My childhood church was Tokaikolo in Granville, a suburb in Western Sydney. The church is named after the first morning star we see in Tonga.

William Dixson

1. A collector of Aboriginal, South Sea Islander, Maori, Fijian, Tongan, Sāmoan and Tahitian trauma.

2. When will our artefacts be returned to us?

This story appears in Openbook winter 2021.

![Detail from Specimens of Native Paper from Tongo [Tonga] and Fiji, sent home by John Hunt, Wesleyan missionary, 1847](/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_280/public/slnsw_fl9177890.jpeg?itok=PL69UboW)