On a sultry late summer day in 1928, visitors to what is now the State Library of NSW were treated to an unusual spectacle: a man in a straight-jacket — his feet tied together with thick rope, his hands handcuffed — was swaying upside down from a crane in the middle of Shakespeare Place.

Australia’s answer to Harry Houdini, magician Murray Carrington Walters (or ‘Murray the Escape King’ as he preferred to be known) was drumming up publicity for his season at Sydney’s Tivoli Theatre.

A few days earlier he had been arrested for obstructing traffic as he prepared for an even more dramatic stunt — escaping from a straight-jacket while suspended tens of metres above a 2000-strong crowd in Market Street. Hauled before a magistrate, he declared he would rather spend a month in Long Bay than pay the £5 fine, boasting that he could break out of any prison cell. Tivoli management quickly stepped in to pay the fine, fearful that their star attraction would miss his shows.

Murray was no stranger to brushes with the law. In London, police intervened to stop him being tied to the hook of a crane 60 metres above Piccadilly Circus. Calcutta’s constabulary took a dim view of his intention to jump off the Howrah Bridge ‘straight jacketed and heavily shackled’ because they feared he would drown in the Hooghly River’s treacherous currents. And in Japan authorities ordered his deportation because of the ‘bad example’ his acts would set for would-be jail breakers and thieves.

To disentangle the story of the Melbourne-born escapologist is to shine a spotlight on the history of Australian magic. Murray grew up in an era when Houdini, Howard Thurston, Charles Carter, Dante (Harry Jansen) and other magicians were among the highest paid and most famous entertainers in the world. Like so many other promising ‘prestidigitators’, Murray was determined not just to emulate his heroes, but to outshine them.

In 1907, Murray’s parents took their six-year-old son to see a performance by Chung Ling Soo, an American trickster whose real name was William Robinson. Soo would later go down in history as the victim of a bullet-catching trick that went tragically wrong. With his flowing silk robes, make-up, waist-length plaited pigtail and East Asian repertoire, he was so convincing that he won the epithet of the ‘Original Chinese Magician’ over Ching Ling Foo, a Chinese man who for a brief period was America’s most successful magician.

Inspired by Robinson’s show, Murray began teaching himself the craft of escapology. When he turned 10, he told his mother to lock him in his room and take the key. ‘In a few minutes he was by my side, ’ she told Sydney’s f newspaper. ‘He said mysteriously, “Don’t ask me how I escaped. That’s my secret. Someday, I will make a lot of money through my knowledge.”’ Recognising his exceptional talents, the Australian Society of Magicians made him the club’s youngest member. Aged 16, he boarded SS Niagara bound for the American west coast, hoping to turn his hobby into a career.

In doing so he joined scores of Australians representing every imaginable genre of entertainment from balladeers to balloonists, Shakespearean actors to sopranos, and circus acrobats to stand-up comedians, playing to audiences in the jungles of Borneo, the Himalayan hill stations of India and the treaty ports of China and Japan. Running this low- tech but highly sophisticated and globalised entertainment industry were business-savvy entrepreneurs like Robert ‘Sparrow’ Smythe, Harry Lyons and JC Williamson.

Murray’s State Library stunt came nine decades after the first-known performance of theatrical magic in Australia. In 1836, Monsieur du Pree, ‘The Wizard of the South’, delighted audiences in Parramatta with ‘some surprising illusions ... such as catching a bullet between his teeth, discharged from a pistol, which may be loaded by anyone, dancing a figure blindfolded among nine eggs placed at certain distances; Ventriloquism &c. &c. &c.’ Under his real name, Thomas Amott, Du Pree had arrived in Australia in 1827 as a convict after being found guilty in the Old Bailey of stealing two pianos and a harp.

The gold rushes of the 1850s were a boom time for entertainers in New South Wales and Victoria. As conjurers arrived from overseas, accompanying circus shows or on their own, cashed-up miners clambered for seats in pop-up theatres from Ballarat to Braidwood. Among the performers was the first magician to tour globally, Scotsman John Henry Anderson, who called himself ‘The Wizard of the North’.

For Anderson and other stage illusionists, strong competition eventually came from the spiritualist acts of the Davenport brothers, Ira and William. Born in Buffalo, New York State, they rode the wave of interest in spiritualism that began in 1848 with the spirit rapping and table turning of America’s Fox sisters. The Davenports arrived in Melbourne in 1876 with a program centred on producing ‘manifestations’ with musical instruments and other objects while they appeared to be securely tied with ropes in a ‘spirit cabinet’. To rule out any form of deception, audience members were invited to tie up the brothers, who would then miraculously escape from their bindings.

Newspaper reports at the time reveal a healthy dose of scepticism among theatregoers. In Ballarat, an audience member bent on debunking their act spent 20 minutes tying the brothers with his own knots and sealing the cabinet. It took less than five minutes for the doors to reopen and for the two men to step out, ‘leaving the ropes coiled behind them, the house fairly convulsed, and the Davenports received quite an ovation’. Exposing spiritualism became a duty for magicians such as Anderson, who used his shows to duplicate the Davenports’ effects and to prove that modern magic was based firmly on science and rationality. William Davenport died in Sydney in 1877 of tuberculosis and is buried in Rookwood cemetery.

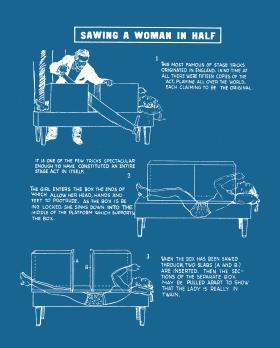

The flow of magicians arriving in Australia also included troupes from Asia. In 1880, Harry Lyons brought the ‘Afghan Museum and Oriental Curiosity Bazaar’ to Victoria. Billed as ‘Cabul jugglers and East Indian Magicians’, the ensemble included Koodah Cassim Bukos, a fire eater, and Buchas Mahomet Khan, a ventriloquist. A decade later, Charles Bastard — described by Calcutta’s Deputy Commissioner of Police as ‘a collector of curiosities and manager of a skating rink’ — unveiled the ‘Museum of Indian Curiosities’. Performers included Painee Pindarrum, ‘a juggler of high order’, who demonstrated the ‘cups and balls’ trick, produced fire from his mouth and spat out dozens of two-inch-long nails. Another headliner was Galip Sahib, who executed the ‘basket trick’ with a young girl named Giddy. Crammed inside a wicker hamper, Giddy screamed as the magician thrust his sword into the container, only for her to emerge unscathed. A few months later, the entire troupe mutinied over pay and conditions and marched on the District Court in Melbourne, bringing traffic to a standstill. They were eventually repatriated to India.

The so-called Golden Age of Magic from about 1880 to 1920 saw most of the world’s greatest magicians tour Australia. Among the arrivals were Thurston, Houdini and Carter, who appropriated a range of Eastern styles. ‘Carter the Great’, as he billed himself, switched between Indian and Chinese characters as he presented acts that included The Séance from Simla, A Night in China and a levitation routine allegedly taught to him by a ‘high caste Indian fakir’. Brightly coloured posters showing him dressed as a Chinese mandarin, an Indian prince, a Mongol warrior, and even a pith-helmeted British soldier astride a camel, were plastered across towns, ensuring packed houses wherever he performed. Originals of the posters now trade hands for thousands of dollars.

Among those flocking to the shows of Thurston and others was the young Leslie Cole. Born in the Sydney suburb of Alexandria in 1892, he became a professional magician in 1910, initially performing escape acts before branching out to bigger, more diverse spectacles. By the 1930s, his signature ‘How’s Tricks?’ show featured more than three dozen performers presenting a range of variety acts.

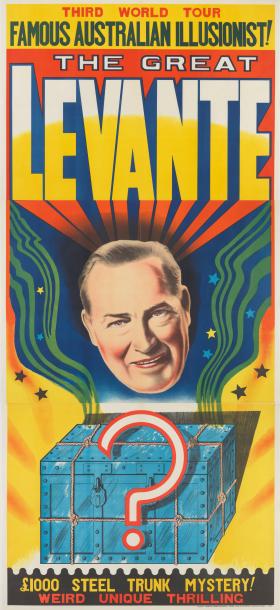

In 1927, adopting the stage name Levante — together with his wife Gladys and their six-year-old daughter Esme, who was billed as ‘the Daughter of the Gods, the Child Phenomena, Mentalist and Crystal Gazer’ — he began a tour of Asia and Europe that would last for almost 13 years. In Nanking, he came across a street act where an elderly man thrust a knife into a young boy’s stomach and then slashed his neck, causing blood to spurt in all directions. Horror-struck, he watched as another performer covered the boy’s inert body with a cloth. When a policeman appeared and threatened to take the magician to prison, the man pleaded that he could restore the boy to life again if sufficient money was collected from the crowd. Satisfied with the takings, he pulled the cloth away. Aside from ‘a few smears of what might be blood, the boy appeared to be quite normal,’ Levante wrote in the mimeographed newsletter Mysteries of the Mystic Seven, adding that ‘I had no solution to offer for [how the trick was done].’ It was only when witnessing a similar performance in Ceylon that he discovered the secret.

In 1939 ‘The Great Levante’ was named as the world’s number one magician by the International Brotherhood of Magicians. Forced by the war to return to Australia, he presented his ‘How’s Tricks?’ show to capacity crowds. ‘[N]obody else was working an illusion show of that scale, and he kept up his reputation as “The Great” even though the post-war years became more and more difficult to run a big show,’ says magic historian and Levante’s biographer Kent Blackmore. ‘Only Maurice Rooklyn approached the size of his show “How’s Tricks?” Overall, everything about Levante hangs off his personality. Onstage he was friendly but the master of his art, and a very impressive, dignified character. Offstage he was everyone’s friend, sociable and easy to approach.’

Esme Levante, who became was one of the principal performers in her father’s shows, began touring internationally in the 1950s with her own magic cabaret act, making her one of the few professional female magicians. ‘It was, and is, a male dominated field, though there were female magicians in Australia dating back to the mid-1800s,’ says Blackmore. ‘There was definitely a “boy’s club” attitude,’ he adds, citing the refusal to admit female members to the prestigious London club, the Magic Circle, as the most obvious example.

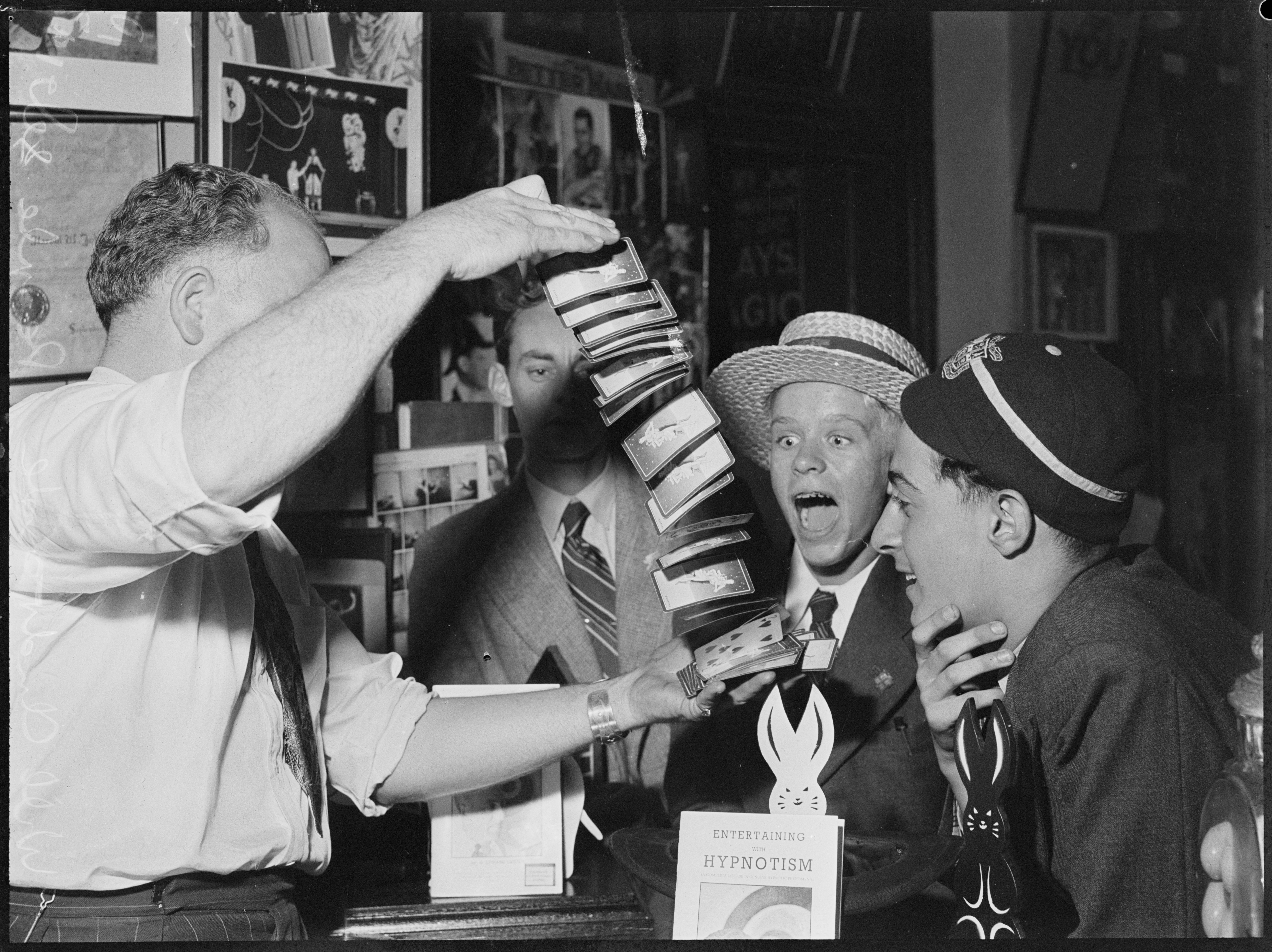

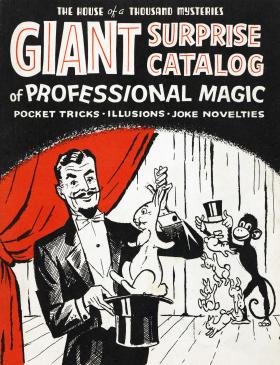

In 1920 Levante founded the Melbourne branch of the Australian Society of Magicians. The society’s journal, the Magic Mirror, was integral to the trade in secrets and encouraged innovation and experimentation. This was supported by stores such as Andrade’s Magic Department, which had branches in Melbourne and Sydney selling books, magazines and magic paraphernalia.

‘If you look back at the 1920s, magic clubs were social groups and communities. They ran regular shows for the public, and social activities such as picnics,’ explains Blackmore. ‘Magic shops, such as Sydney’s “Weirdo’s” or “DeLarno’s” were places for beginners to meet new people, trade ideas, get personalised advice on what sort of tricks were suitable.’

Although the widescale uptake of television in the 1960s took a toll on live magic, Levante continued to perform until shortly before his death in 1978. During his career he amassed the vast collection of books, pamphlets, journals and posters that was acquired in the early 1960s by one of his students, Robert Robbins, who performed under the stage name of Robert Merlini. In 1967, the collection was purchased by the State Library of NSW.

Sydney-based magician Adam Mada describes the Robbins Stage Magic Collection as ‘a real and tactile connection to the past, to a time when magic, magicians and wonder workers were a dominant form of entertainment’. He adds: ‘I find it fascinating, reading about tricks and illusions and basic principles well over 150 years old which are not only relevant in my work today, but will still readily fool a modern audience.’

Having worked as a magician for almost 20 years, Mada has seen his profession undergo enormous changes. ‘Magicians will now create specific content that will only ever be consumed in quick bite clips through social media and would never work in real life. This was always a major bone of contention in the past between magicians who worked live and those who began to explore television. It’s the same bone with the rise of the social media magician.’

Embracing changes in technology has always been the lifeblood of the magician’s craft. The smoke and mirrors used to project ghosts onto the stage in the early 1800s had by the end of the century progressed into elaborate pulleys and invisible wires that would send a magician’s assistant soaring above the audience. ‘We magicians have an uncanny knack to adapt, embrace and flourish with social and technological developments,’ says Mada.

That ability to adapt was recently put to its most severe test since the Depression of the 1930s wiped out most of the vaudeville industry. Mada believes the Covid-19 lockdowns that closed live performance venues across Australia in 2020 will go down in history for heralding the rise of ‘digital magicians’ using live stream performances to engage with their audience. ‘The take up has been phenomenal, with audiences being able to interact in real time through their screens from home with magic created specifically for this new medium,’ he says. ‘Magic has never been more alive and accessible, and this is pushing incredible innovation.’

John Zubrzycki is the author of Empire of Enchantment: The Story of Indian Magic (Scribe). He is the 2021 Merewether Fellow, researching Australian popular culture in Asia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2021.